Variants are claims that are similar to each other in at least one of a set of measurable ways. The variant mesh is a fabric of mutual references between claims that are ordered along each of a set of predefined axes that the system supports. Claims only reference their immediate neighbours on each axis; the entire structure is like a multidimensional linked list, or mesh. The relations in the variant mesh are slightly different from the relations in the regular claim graph in that they are less relevant to users. Instead, they exist primarily to support computations that permit the management of large numbers of nearly-duplicate claims.

Context (e.g., dates, locations), specificity, and phrasings (perhaps ranked according to a set of usefulness heuristics), could all be handled as types of variants. The idea of ordering claims along these axes in a mesh structure gives us a framework to think about how to handle them and may take us some of the way to solving the combinatorial problem of claims.

Adding a variant to the mesh

- Established that a new claim is a variant, either by graph search or by using local knowledge from the node that’s been explicitly branched from.

- Ask LLM to identify all supported variant axes on which the two claims have some variation, and to identify the directionality of the relations.

- Add references between claims as appropriate.

Copying relations to a variant

When adding a new claim that is a variant of an existing claim, you want to borrow some of the relations from the existing claim and attach them to the new claim. However, only the relations that actually apply to the new claim should be copied — a subset that depends the particular differences between them the new claim and its variant.

A process for copying only the relevant relations could look something like this.

- Let’s say we’re working with one new claim (A) and one existing, variant claim (B). For each claim (X) that references B, ask an LLM: “if X is true for B, would it also be true for A? Respond with yes or no.”

- For every “yes”, duplicate X and point it to A instead of B. Recursively repeat steps 2-3 for all claims referencing X.

The variant explorer

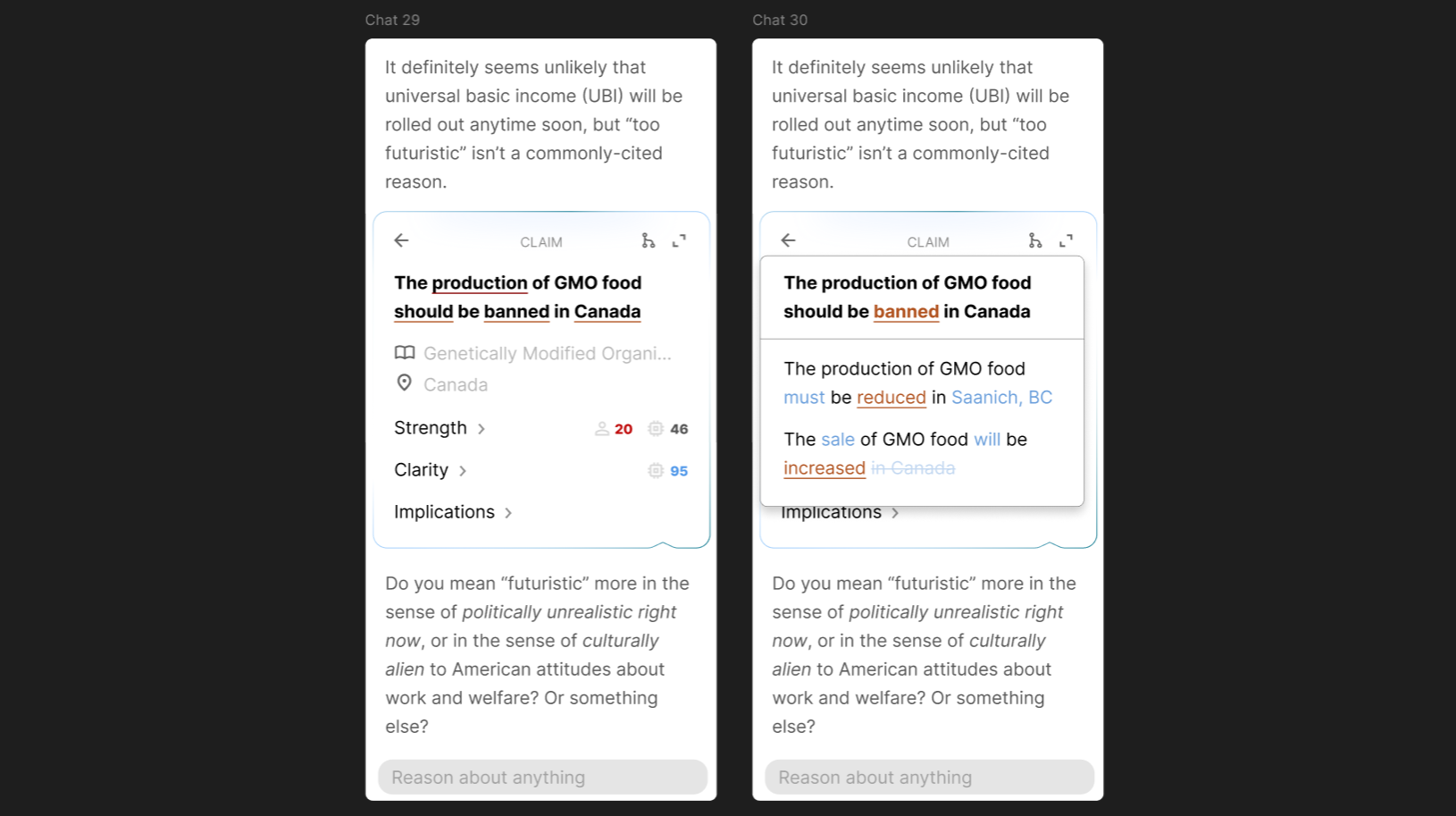

The variant explorer is the piece of user interface that is used to navigate between variants. I think it can basically just be a dropdown under the title of the node. When you click a word in the title, the explorer opens to show variants with a different word in the corresponding part of the sentence.

Ultimately, it probably can’t be this simple. The problem of identifying corresponding words in claims may not be trivial. Significant rephrasings might capture similar meanings, and thus still be variants, but might be very different to represent in an interface like this. I suspect that the full solution will provide a way to navigate variants by sentiment as well, e.g., pro/anti-GMO, and perhaps other axes.

Anywhere that variants are listed in a dropdown, they should be ranked partly according to how similar they are to the origin node but also according to how strong they are. Very unclear or low-strength claims should be put near the bottom. You may also want to show a number for claim scores next to each variant inside the dropdown. If you end up with a lot of variants, you could also look into adding a scroll bar inside the dropdown.

Ultimately, it probably can’t be this simple. The problem of identifying corresponding words in claims may not be trivial. Significant rephrasings might capture similar meanings, and thus still be variants, but might be very different to represent in an interface like this. I suspect that the full solution will provide a way to navigate variants by sentiment as well, e.g., pro/anti-GMO, and perhaps other axes.

Anywhere that variants are listed in a dropdown, they should be ranked partly according to how similar they are to the origin node but also according to how strong they are. Very unclear or low-strength claims should be put near the bottom. You may also want to show a number for claim scores next to each variant inside the dropdown. If you end up with a lot of variants, you could also look into adding a scroll bar inside the dropdown.

Scratch pad

Localized axes

Maybe the axes of the variant mesh only apply locally. This facilitates the specific kinds of comparisons that are needed between similar claims without bogging down the entire mesh with every possible axis of comparison.

Augmenting LLMs as function calls with heuristics

A lot of the functionality that this system needs may be unlocked with algorithms whose building blocks are specific pieces of natural language processing functionality outsourced to LLMs. The behaviour of these functions could be shaped using lists of heuristics, e.g., as for what makes a strong vs. weak claim, that help the LLM reason in the way that we want. These heuristic parameters would give us some leverage to refine the way that the system works over time.

Related claim search with auto-generated specificity hierarchies

Get an LLM to rewrite claims in several levels of generality higher than the way they were originally written. Add these as hidden claims into the variant mesh. Then, use the text of these claims to find possible duplicates. The idea is that, though the specific text of claim variants or duplicates might not match very well, the text of their more general variants are likely to match. Even if you find a match a few levels up, you can use the match to narrow your search a lot.

Distill simplified claim versions to support automated reasoning

For reasons related to implementation difficulty, it may be desirable to maintain a separate, hidden version of each claim wherein it is reduced to a simple sentence, sacrificing nuance to make the implications easier to automatically reason about. Consider the claim 01 | A universal ban is not the right approach to addressing any potential problems with genetically modified foods that is connected to 02 | The sale of genetically modified foods should be banned. Claim 01 is essentially saying “the sale of genetically modified foods should not be banned” — a straight counter to 02. It adds some nuance by acknowledging the concerns around GMO and conceding that action is not out of the question while also flatly rejecting 02. Maybe this simplified version would be easier to do comparisons with in the variant mesh.

Pending technical questions

- How to define what is and isn’t a variant (i.e., the strict definition of variant, including the specific axes of comparison) and thus what the conditions are for running the LLM query to set up variant axes and directionality.